Overarching Philosophical Themes

What would two contrasting fates look like? How does one navigate a turning point, a revelation?

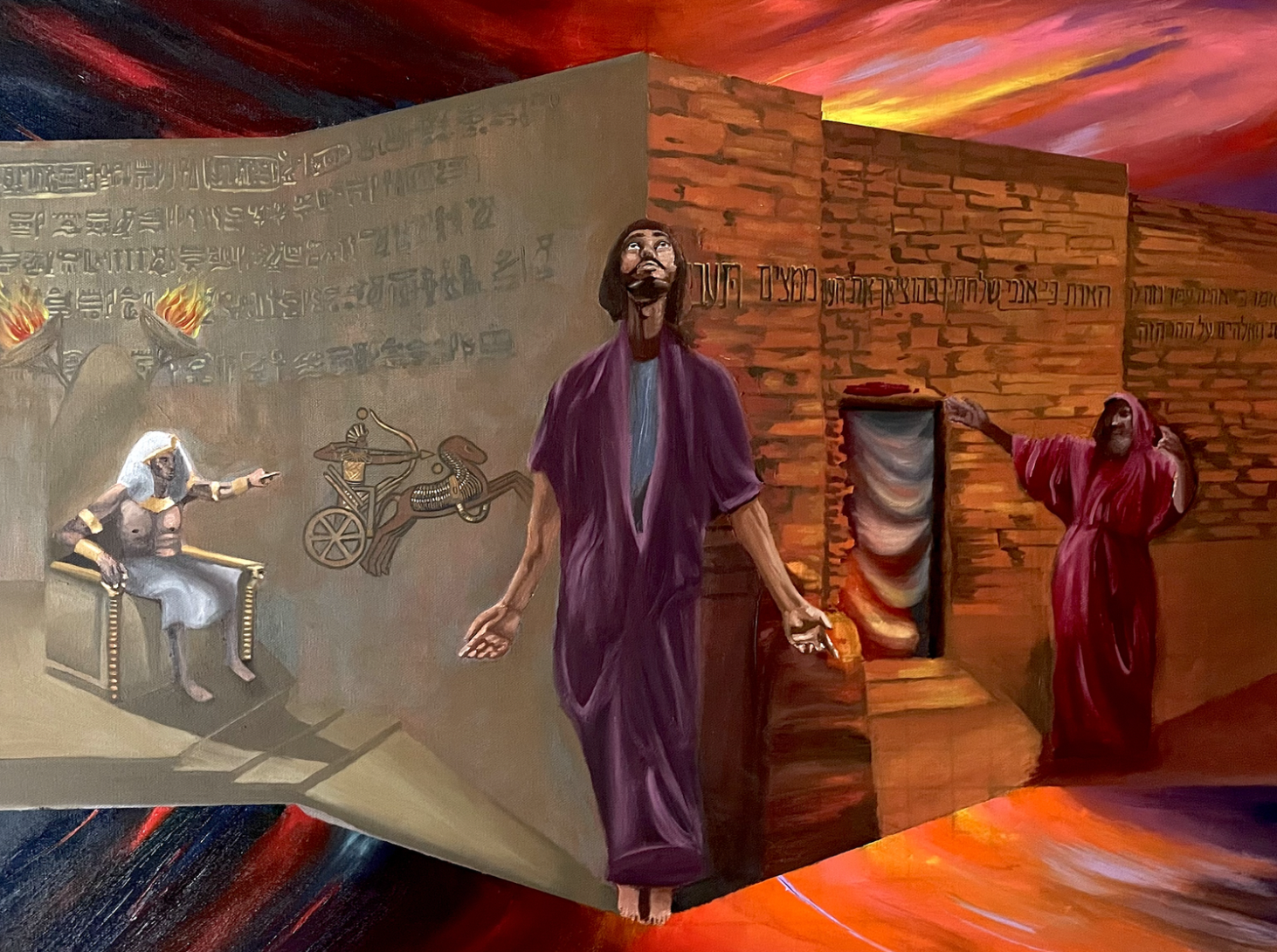

In this painting, I'm blending the recognizable story of Moses as written in the "Book of Exodus" with the depiction of Moses in the classic movie "The Prince of Egypt" to further explore questions of Fate, Faith, Loyalty, and Love.

Who are the subjects?

(Note: "The Book" refers to the "Book of Exodus," and "The Movie" refers to "The Prince of Egypt.")

MOSES: The main character through whose eyes we read and experience this story is Moses. He is painted in the center, the first place to which a spectator's eyes fall. His physical placement in the middle of his brothers symbolizes the mental struggle of also being placed between the two paths his brothers represent. In the Book as well as in the Movie, G-d comes to Moses when Moses stumbles upon a burning bush, at which point G-d enlightens Moses as to the responsibilities ahead to free the Israelites from the hardships bestowed by the Egyptian Pharaoh. The anxiety comes to Moses in the Book from his own self-doubt, questioning whether or not he could rise to the occasion and fulfill his obligation. The turmoil comes to Moses from the Movie in searching for a way to protect both his brothers through irreconcilable forces.

PHARAOH RAMSES II: In the Book, there is no mention of a specific Pharaoh, but historians and theologians who map the Exodus story to the world's historical timeline believe this would have been during the reign of Pharaoh Ramses II. In the Movie, Moses is raised alongside Ramses as his younger brother, the Prince of Egypt, not knowing he is actually a Hebrew. Even upon this revelation, his bond to Ramses doesn't break, and throughout his journey in leading the Israelites to freedom, Moses tries multiple times to convince his brother, the Morning and Evening Star of Egypt, to change his ways. The painting shows Ramses not only as a Pharaoh who sits upon a throne, but also as a man surrounded by a history and context (portrayed by the hieroglyphs) that require him to act in the interest of his people, to strengthen and maintain the dynasty. In this way, both Moses and Ramses are called to a purpose higher than themselves and their bond.

AARON: As Moses' biological brother, Aaron plays a major role figuratively and physically. In the Book, when Moses is doubting whether he could lead the Israelites out of Egypt, he suggests to G-d that perhaps Aaron would be better for the job, as Aaron was more well-spoken. This resulted in a joint effort between the two brothers, but Moses would not be separated from this moral duty. In the Movie, while Aaron plays a smaller role (especially compared to Miriam, their sister), Aaron is still the one who keeps Moses motivated. Though Aaron was skeptical to Moses' intentions in the beginning, Aaron was the first one to walk through the sea Moses had parted. They are painted dressed in similar robes, symbolizing covering their individualities to act together in the way upon which they were called.

Deciphering the Hieroglyphs and Their Relevance

Historical accuracy in surrealistic interpretations is fundamental to grounding the story not only in reality but also in relatability to the spectator.

Unfortunately, much of the meanings behind hieroglyphs are lost in translation, but experts, in collaboration with locals preserving the culture of Coptic language and grammar, are able to piece some things together.

I'm only going to mention the research that relates to my painting, but I encourage anyone to take that deep dive, if it interests you. The main question I explored was what the ancient Egyptians wrote about during Pharaoh Ramses II's reign.

From my understanding, the subject matter depended on the location of the hieroglyphs. Temple walls held a different purpose than those in a tomb, those externally facing civilians, those constructed alongside statues of pharaohs, etc. The hieroglyphs in this post were graciously sent to me by Egyptologists Dr. Josef Wegner and Dr. Jennifer Houser Wegner here in Philadelphia, and these depicted hieroglyphs can be found at the Luxor Temple.

The Luxor Temple is located on the east bank of the Nile River, and what makes this temple special is the intention of its construction. It is the only temple that is dedicated to the "rejuvenation of kingship," and many, many rulers contributed to its construction over time, including Ramses II.

Hieroglyphs during Ramses' time seem to either portray "propaganda," for lack of a better word, and/or his intentions as a ruler. They often depict Ramses victorious in battle. I wanted to include not only the written hieroglyphs but the famous carving of Ramses in battle to show this ambiguity of time, of past, present, and future, as Ramses has the responsibility to always perform his duty, one that expects nothing but Greatness and Fortitude.

As my project here is to explore the concept of Fate, my intention with this side of the painting is to show all the contributing factors that sculpted Ramses. Were these self-fulfilling prophecies? Was the story unfolding over time or already written?

What does Moses' Body Language Symbolize?

Moses stands in the center of the painting, equidistant from Ramses and Aaron. The setting also reflects this division between the two brothers by being the corner at which two very different walls meet. And as you know, this project is my way of exploring the philosophical question, what happens at the intersection of two seemingly opposing fates?

Before I solidified this representation of Moses, I was playing with several ideas. Sharing them adds to the weight and importance of how he currently stands.

First, I considered painting his body slightly to his left, pressed against the red/orange wall, on the same side as Aaron. His body and feet would be planted on that side, while his neck and right hand would extend in the direction of Ramses. This was to show that he had no choice but to follow G-d's orders, though he was broken-hearted and afraid to leave behind Ramses. Such an agonizing reach-around-the-corner would also be a nod to the movie, because Moses ultimately had to leave Ramses behind.

What prevented me from this composition was the possible interpretation that Moses was forced to leave behind what he knew. Force doesn't have to have a negative connotation, and especially in the realm of exploring fate, it's probably more fitting than not. However, if Moses is the center of the painting, suggesting we should see ourselves to some extent in him or understand the story through his eyes, I don't want to be promoting force.

My second idea was for Moses to sit on the ground with his head against the wall. This would create a "V" shape between himself and his brothers to highlight the weight of revelation. However, 1) I didn't want Moses looking exhausted/defeated, and 2) I didn't want a "downward" portrayal of fate or Moses' story.

This second realization helped me solidify the way Moses currently stands, which is tall, accepting, and with his head aligned with the scripture as opposed to his brothers.

Let's break down how Moses' posture further explores the aforementioned question of fate.

The direction of the subject's gaze is crucial in understanding the story behind a painting.

Each man’s gaze in my painting plays a vital role in telling the story. I'll leave it to your imagination to interpret what it would mean if Moses was looking directly at the spectator, at either of his brothers, or at the ground. But now, I'll tell you why he looks up.

The moment of revelation required a faithful surrendering. Acceptance in his role to lead the Hebrews out of Egypt meant letting go of who he thought he was and could be. In the Book, Moses tells G-d that he doesn't feel suited for the mission because he isn't a good orator: who would believe him? G-d had to remind Moses that he was chosen for a reason, even if that reason wasn't fully understood by Moses. Therefore, Moses looks up to surrender to his faith, even when he doesn't fully comprehend how he'll free the Hebrews and go against the Pharaoh.

Simultaneously, looking up (and even figuratively, looking to G-d) helps keep earthly distractions at a minimum. He does not see the rage of Ramses or the comfort in Aaron.

Moses' outstretched hands play a similar role. His palms face upwards, indicating his openness to receiving direction from above. I also wanted to have a balance between the two brothers, because the real tension and tragedy lies with the fact neither brother means more to Moses than the other. If he could have it his way, he would reach out to save both.

The evenly stretched out arms also show that neither Ramses' nor Aaron's words have a greater effect or "pull" on Moses, but G-d's words alone will lead him.

If you look very closely, you'll see the tip of Moses' index finger (the hand facing Aaron) is slightly bent upward, indicating that subconsciously, he has already agreed to join Aaron in freeing the Hebrews. A closed fist would be too glaringly obvious, but the curling of his index finger is just enough to leave a hint.

Lastly, Moses feet are side-by-side and barefoot. When Moses stumbled across the Burning Bush, G-d told him to take off his shoes, for he was standing on Holy Ground. To mimic that Moses had completely surrendered, I wanted to mirror this respect.

The closeness of his feet help give him a tall, linear figure, like the staff with which Moses was able to perform G-d's miracles.

Exploring the Idea of Sacrifice

This topic is something I can spend countless hours unraveling; its intricacies and complexities are limitless because the context in which a sacrifice exists is always supra-rational, or beyond reason.

Although my intention with this painting is to explore Fate and Faith through a philosophical lens, the element of sacrifice has become prominent in every aspect of this painting.

Such is the beauty of art as meditation: the answers present themselves in a way that was already within you.

Because the relationship between Fate and sacrifice is a new revelation for me, I apologize if my thoughts aren't as cohesive. And, I could very much be wrong and misinterpreting what I'm seeing.

My painting is called "The Writing on the Wall" because as I mentioned, my project is to explore the intersection of two seemingly-opposing fates. The hieroglyphs and Pharaoh Ramses II represent the fate of Egypt, and the Scripture and Aaron represent the fate of the Hebrews. The "fates" meet through Moses, who looks upward to G-d for ultimate guidance in fulfilling the prophecy.

How does the concept of sacrifice show itself in each aspect of this painting?

Ramses II is dressed in Pharaoh's clothing. The garment on his head is called a Nemes and represents not only royalty but also being the commanding voice and leader of a dynasty. In other words, Ramses isn't acting as Ramses; he acts as Pharaoh, with his ultimate mission being upholding and strengthening the dynasty at any cost, including personal interests and sentiments. As you can see from one of the screenshots where the statue of his father mirrors Ramses' face in the distance, Ramses has his work cut out for him.

This sacrifice is a sacrifice of oneself for a greater purpose. So where did Ramses go wrong? He followed in the footsteps of his father, and his father before him, etc. My guess is his anger led him astray, which means that a true sacrifice of oneself cannot be done with anger.

Think about the last time you were angry. It's a very consuming feeling, sometimes colloquially described as "seeing red." Our hearts are pounding, our neck veins are popping out, and our lips are tightening. Think of how many muscles and how much energy we use when expressing anger.

A sacrifice requires the removal of our own desires, and when we're angry, we are very much thinking of ourselves. So while Ramses thought he was acting as Pharaoh and on the surface we may empathize with Ramses for being constrained to a lifestyle he didn't choose, he ultimately chose to act solely out of self-interest, resulting in the collapse of the dynasty.

We then turn to Aaron, who is painted with an open hand gesturing to the sacrificial lamb blood painted over the doorway. G-d told Moses that He would pass over the people of Egypt, slaying the first born sons of those who fail to brush the blood of a lamb over their doorway as a sign toward their faith in Him.

A sacrificial lamb is no stranger to a story from the Old Testament.

But what sacrifice does Aaron represent in this painting? Remember, he points not only to the blood on the door, but also to G-d. His sacrifice is a surrendering in faith.

Moses shows the ultimate sacrifice in the center of this painting, because he is painted with barely an inclination toward either side, even though his mind and his heart could justify reasons for sticking beside either brother.

What does this say about the relationship between sacrifice and fate? I think I'm starting to understand that we all sacrifice ourselves to something (an emotion, a mission, a purpose) or someone (our family, our friends). But there is one kind of sacrifice, the one hardest to achieve, the ultimate sacrifice, which is a complete surrendering to Someone Higher.

I don't have the answers as to how one makes this sacrifice. I've heard theologians say that G-d shows Himself to specific people, and all we can do is be open enough to receive Revelation. This is why Moses is shown with open arms, and Aaron points upward.

Fate remains merciless, though. By understanding the nature of sacrifice, we can better understand ourselves, and maybe, detach from things that are pulling us away from being more open and receptive.

How to Read the Painting

As you know, my paintings are visual stories, and just like a story, there's a way to read this painting. However, unlike the traditional black and white print on a page, you can read my painting in many ways, from different directions.

Let's start with the classic Western way: from left to right. Both the sky and the subjects transition from dark to light as your eyes move across the canvas. This transition mirrors the path of enlightenment. Ramses is in a dark room, surrounded by dark walls, engulfed by a night sky with jarring streaks of scarlet red. The hieroglyphs behind him give this implication of something divine and royal, but notice that the majority of the hieroglyphs are covered in shadow. The carving of Ramses on the horse riding into battle is also entirely cloaked by shadow. As our gaze moves to the right, we see Moses. The light direction on Moses comes from above, but he's draped in the darkest clothing. This creates a 50/50 balance between light and dark in the middle of the painting. Even his face: the majority of it bathes in light, contrasted directly by his dark hair and dark features. As we continue with the idea that we're "reading the light direction" so to speak, moving from ignorance to revelation, Moses is indeed at the crossroads. Once we reach the outside, directly under the brightest yellow parts of the sky, greeted by Aaron with open arms, we see how revelation is portrayed in contrast to ignorance.

We can then read the painting by analyzing the two light sources. One is from the sky, most notably to the right, and the other derives from the fire behind Ramses, on the left. One is man-made, the other is natural. One is directly beside the subject, the other is unreachable. One is extinguishable, the other isn't. When we relate this to the themes of ignorance and revelation, we see that ignorance is created and must be actively maintained, while revelation, once it happens, is ever-present and can't be diminished.

Next, I want to turn your attention to the writings themselves. The hieroglyphs, as I mentioned, are mostly in shadows. They look two-dimensional and barely legible. Only the hieroglyphs closest to Ramses, closest to the man-made fire, are highlighted by the flames. What happens when Ramses leaves and the fire goes out? The hieroglyphs would disappear. Though experts are unable to translate all hieroglyphs for their meanings, we know that hieroglyphs were used for both recounting of historical events and for promoting and/or predicting the successes and virtues of the Pharaoh. Let's compare this to the Hebrew writing on Aaron's side of the painting. They are highlighted by the sun rising behind them. The scripture reaches Moses, touches his ear, as opposed to the large gap beside the hieroglyphs. The Hebrew writing also spans over three walls, not just two. This symbolizes the extent and longevity of the passage.

Notice too, that Ramses doesn't point to the writing; he points to a carving of himself riding into battle, which points to Moses, almost as a target. Aaron, on the other hand, points to the scripture and toward G-d, both in an upward motion. And which is more inviting?

My favorite way to read the painting, and the one with which I resonate most, is if you divide the painting horizontally in half. The composition is such that the lower half of the painting includes Ramses, his carving, Moses' hands, the doorway marked with sacrificial blood, and Aaron. The top half of the painting includes only the writings and Moses' head looking up at G-d. It's a complete separation between earthly matters and that of the divine. Since this painting was initially created to philosophically explore the idea of Fate, I wanted to make sure that the majority of the painting reflected something of that nature, something bigger than us.

Therefore, if you read the painting from the top to the bottom, or from a bird's eye view, you see that G-d "comes down" through scripture to be interpreted by people. The Hebrew excerpt depicts the moment when G-d comes to Moses through the Burning Bush and assures that He will help and protect Moses as he frees the Hebrews out of Egypt. Notice how the writing reaches Moses' ear, and Moses looks up, because at that moment, he had a direct line of communication to G-d.

A common theme in theology is the distinction between cosmic and earthly matters, specifically that earthly matters pose as a distraction to that which is divine. The tension pictured here which Moses experiences emerges from the fact that he has to choose between his two brothers. There isn't a tension when one operates in the realm of the divine, which is why we know that ultimately, it wasn't really a choice for Moses to make.